Blazor is an exciting new web framework from the ASP.NET team that uses Razor, WebAssembly, and Mono to enable the use of .NET on the client. There’s been a lot of excitement about the possibilities this presents, but there’s also been just as much confusion about how these various parts fit together. In this post I’ll attempt to clarify things and show you exactly what each of these technologies do and how they work together to enable .NET in your browser.

How JavaScript Works

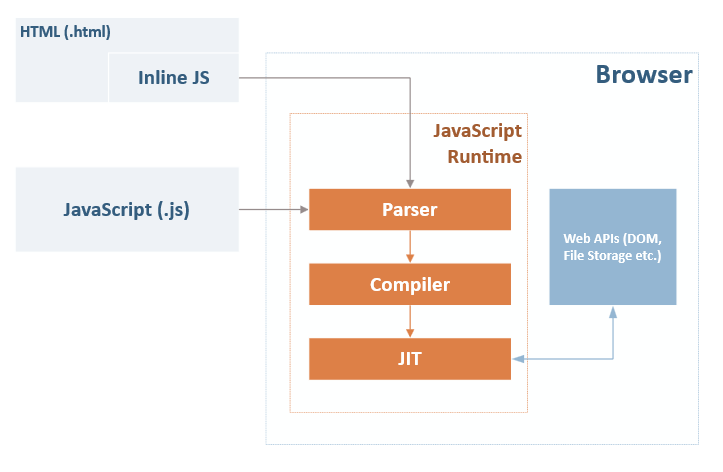

Before we start examining some of the more recent pieces of this puzzle, it’ll help to take a step back and look at what happens inside your browser when it loads and evaluates JavaScript code:

Inside every browser is a JavaScript runtime (or engine) that's responsible for turning your JavaScript into something that can be evaluated. It's often referred to as a virtual machine since it presents a well-defined boundary in which the code is evaluated and isolates that evaluation to a specific sandboxed environment. This diagram is a gross oversimplification of modern JavaScript engines, but they all generally consist of three stages:

- Parser - Performs lexical analysis on the JavaScript code and converts it into tokens (small strings with specific meaning). The tokens are then reassembled into a syntax tree that gets used in the next step.

- Compiler - Transforms the syntax tree into bytecode, which is a low-level representation of the code that the interpreter can quickly understand and evaluate.

- JIT - A just-in-time interpreter that takes the bytecode and evaluates it on the fly at runtime, thus executing your code.

I'm sure I've misrepresented or totally missed certain subtleties of this process, so if you see anything glaringly wrong please sound off in the comments. The important point here is that the JavaScript engine that exists in every browser takes your JavaScript code, figures out what it means, and then evaluates it inside the browser.

How WebAssembly Works

WebAssembly is described by the official site as:

"WebAssembly (abbreviated Wasm) is a binary instruction format for a stack-based virtual machine”

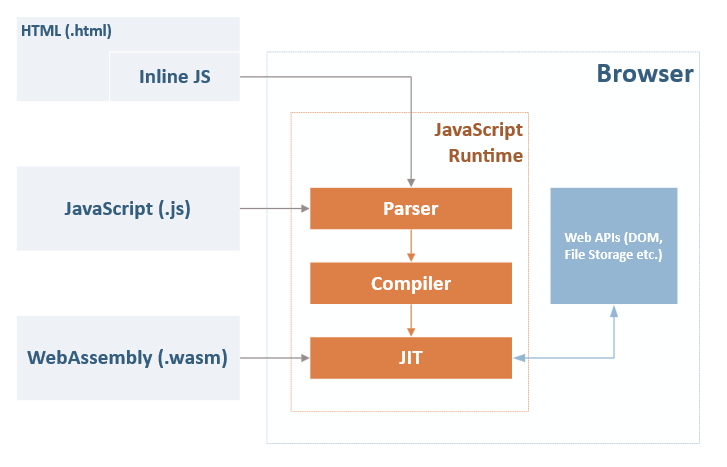

That’s not particularly helpful since it’s intentionally abstract to allow for future implementation changes. What’s important for our purposes is to understand how WebAssembly interacts with the existing JavaScript support that’s already in your browser. Here’s that chart again with the addition of WebAssembly bits:

The thing to notice here is that the WebAssembly code is fed directly into the JIT compiler of the JavaScript runtime. That's because WebAssembly modules have already been compiled into a form of JavaScript bytecode that modern WebAssembly-supporting JavaScript engines can evaluate in their JIT component. The takeaway here is that WebAssembly is related to JavaScript as it pertains to runtime evaluation, but isn't itself JavaScript. This is a common misconception. WebAssembly is not a transpiler like TypeScript, CoffeeScript, etc.

Mono

Recall that I mentioned Mono at the beginning of this post. It’s arguably the most important part of the .NET-in-the-browser story but it’s probably also the least understood.

In order to evaluate .NET assemblies in a web browser, we need something that's been compiled for WebAssembly that knows what to do with .NET assemblies and IL. In other words, we need a .NET runtime that's been compiled to WebAssembly. When Blazor was first starting out, Steve Sanderson found that he could compile a small, portable, open source .NET runtime called DotNetAnywhere to WebAssembly without too much trouble:

Blazor runs .NET code in the browser via a small, portable .NET runtime called DotNetAnywhere (DNA) compiled to WebAssembly

Unfortunately that didn't scale very well. Thankfully for us, Microsoft already owns an open source, cross-platform, highly-portable .NET runtime. No, not .NET Core. I'm talking about the other open source cross-platform .NET runtime: Mono. Even better, the Mono team had recently accounced they were working on getting Mono to compile to WebAssembly.

While the Mono team continues to address bugs and corner cases, the runtime already works very well on WebAssembly. One important point is that this still has nothing to do with Blazor (other than maybe some incentive). The Mono WebAssembly runtime is totally independent of Blazor and can be used by anyone to evaluate .NET assemblies in the browser. In fact, other projects like Ooui have already started to leverage it.

It's also important to note that this is a full .NET runtime that evaluates .NET assemblies. Unlike the WebAssembly support that compiled languages like C++ and Rust are exploring where the application itself is compiled to WebAssembly, the Mono bits are the only thing that needs to be compiled to WebAssembly. Your own .NET assembly will "just work" when it's loaded and interpreted by the Mono runtime. All that said, the Mono team is also exploring a precompilation scenario for enhanced performance. In that mode, you would essentially compile your .NET code along with the Mono runtime directly into WebAssembly bytecode.

Blazor

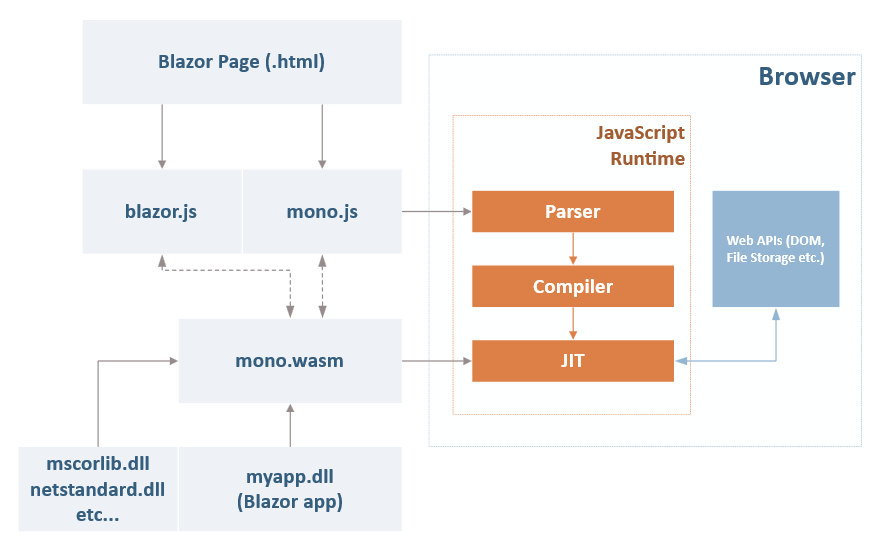

All of this sets up the exciting work going on in Blazor itself. Blazor is the name of a project that includes both a runtime component and various tooling. The tooling helps produce the assemblies that the runtime bits know how to work with. What gets delivered to your browser looks like this:

There's a lot going on here so let's examine each part:

- Blazor Page - The HTML file that Blazor produces is really simple. It basically just includes CSS files and headers as well as a couple JavaScript files to help bootstrap the WebAssembly support (WebAssembly modules currently have to be loaded by JavaScript).

- blazor.js/mono.js - These JavaScript files are responsible for loading the Mono WebAssembly module and then giving it your Blazor application assembly. They also contain support for features like JavaScript interop.

- mono.wasm - This is the actual Mono WebAssembly .NET runtime that

mono.jsloads into the browser. It is basically Mono compiled to WebAssembly. - mscorlib.dll, etc. - The core .NET assemblies. These need to be loaded just like any other .NET runtime otherwise you'll be missing key parts of the .NET

Systemnamespace(s). - myapp.dll - Your Blazor application which was processed by the Razor engine and then compiled by the Blazor tooling. Today the tooling exists as MSBuild tasks that get added to your project by the Blazor NuGet package.

The end result is Razor and C# in your browser! To learn more about Blazor from a developer perspective, check out https://learn-blazor.com/.